Is low-carb necessary for fat loss? Part 2

Want to hear something interesting about research?

It can't take into account every single variable.

When looking at nutrition research, there are so many factors that impact the results. Sure, maybe you gave the subjects a certain dietary protocol to follow but what about people under/over reporting their food? What about psychological stress? How about people dropping out of the study or simply lying about what they're doing? On the researcher end, they might not equate calories or protein, or the guidelines they use for "low carb" or "low fat" might not be anywhere close to what practitioners would use.

In addition to things simply being out of the researcher's control you need to understand whether the study itself was conducted in a way that is essentially "fair" to the results. If you compare two dietary protocols and one is easy to follow and one is extremely difficult, then it won't be a surprise when the easy one gets better results. Not very good for validity.

So how do we know if the research we're quoting was even conducted in a way to ensure the data is useful or accurate?

Enter Professor Christopher Gardner

In part 1 we looked at the science itself to help dispel whether we NEEDED to go low-carb to see fat loss. And the science is getting clearer and clearer that (with the exception of diabetics) you can eat a fair amount of carbs and lose fat. Nice!! If you haven't read it yet (because the last sentence was a pretty broad statement) Part 1 deals with the science side of this right here.

The DIETFITS study was created by Christopher Gardner, a Stanford professor and researcher. In the quest to get some really solid, scientifically valid AND practically applicable date, he and his team looked at the following:

-Genetic predispositions in genotype for low-carb, low-fat or neither. Essentially, does you genetic code predispose you to doing better on a certain dietary protocol? (keep in mind there are thousands of genotype variations, they just looked at a few big ones)

-Insulin resistance and insulin secretion data among the individuals in the study. In other words, how sensitive are you to insulin and how much do you secrete in response to ingesting carbohydrates?

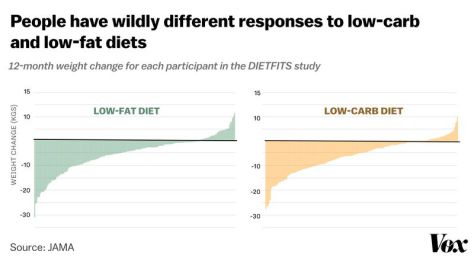

-Weight lost between groups and between individuals. Clients ranged from 60lbs lost to 20lbs gained individually. Keep in mind some people come with psychological baggage and do not follow the plan, hence weight gained. Or they may have simply been assigned a protocol that did not work well for them.

-The group difference in low carb vs low fat saw only a ONE POUND difference on average. That means even though from client to client the changes were wildly different, the group average had almost the same weight lost.

What about the clients?

The DIETFITS team had the subjects attend 22 (yes, 22!!) night classes taught by dietitians educating them on how to implement the diet assigned to them. Essentially giving each person the highest chance of success by educating them on what their doing and giving them strategies to succeed.

Clients were encouraged (across the board) to limit sugar, processed foods and refined grains. They also encouraged them to eat lots of veggies. From there, they were led to the strategies needed for their assigned nutrition protocol.

Clients were taught that there was no right or wrong, good or bad diet assigned. One key factor is making sure people are engaged, do not have poor expectations or set them up for failure.

Assigning the diets

One really interesting thing the researchers did was work on Limbo, Titrate, Quality.

The baseline protocols were this:

Limbo

Low Carb group: Try to eat no more than 20g carbs per day

Low Fat group: Try to eat no more than 20g fat per day

The really smart thing about this approach was that they KNEW people could not go that low. But in assigning a very extreme restricition it would encourage clients to toss out and limit all the foods that would negatively impact their protocol. Essentially each client would fall somewhere along a spectrum which researchers could then guide them to a reasonable number.

Basically it's like if I told you to test your vertical jump - instead of saying "lets see how high you can jump" I told you to "jump to the top of this telephone pole". I know you can't do it, but it encourages you to give it your all, which I can then measure as your baseline.

Titrate

Clients were now told to start from whatever minimum number they could hit from the 20g assignment and add 5-15g per week until they reach an amount that is the minimum they can sustain, feel satiated and are not stressed about.

What's great about this is that Limbo forces the clients to psychologically anchor themselves to the protocol. Titrate allows them to find the minimum that works for their lifestyle and personality.

Some people could do 75g per day, some needed to Titrate up to 125g. This is absolutely genius because it takes into account the fact that if you assign a very rigid diet, some people will fail because they can't adhere but this is NOT the same as the diet not working.

When we look at research saying that a certain dietary approach works better than another, the big follow up is "yes, but can people actually execute this or is it just successful theoretically?".

Quality

No specific calorie counting or assigning strict regimens per meal for these clients; instead they focused on food quality, fiber, veggies and choosing foods that helped them feel satisfied and full.

Things you need to know

There are some amazing things revealed here.

Out of the 609 people:

1. 304 people were assigned to one group and 240 completed the study

2. 305 people were assigned to the other group and 241 complete the study

Adherence

What is revealing here is that this data shows an almost exact adherence and completion rate for both groups. Remember what we said about a diet needing to be sustainable? Having the completion rate almost identical removes the bias that one diet was inherently harder or easier than the other. All the naysayers who might claim "that only worked because one of the diets was too hard to follow" can check the stats and see that they were equally successful. WOW.

Genotype and Insulin

Genotype pattern did not show any difference in weight lost. Noted in the beginning there are thousands of genes but the ones tested did not show any favorability. Since there are so many variables in terms of genes, science can't yet tell us what exact diet works for us. And data from this study shows that as well. The same goes for insulin secretion which means even though some people secrete more insulin than others for the same carbohydrates ingested, it did NOT results in better or worse fat loss.

Calories

Clients in this study reported on average a 500 calorie reduction across the board.

Low carb or low fat?

Protein? Carbs? Fats?

Fiber?

Saturated vs unsaturated fat?

Genotype?

Preference?

Insulin secretion?

ALL DIFFERENT.

But the main commonality? A 500 calorie reduction between both groups and among individuals. So by focusing on food quality and following some general guidelines, people actually found their own path to a deficit that resulted in weight lost.

What is fascinating is that all the variables below calories (like protein, fiber etc listed above) varied so much from person to person. And you would expect there to be other defining commonalities too, such as "high fiber led to more weight lost", but it didn't. The real driver here was the calorie reduction and people managed to work it out on their own by following some basic guidelines.

Wrapping it all up

Low carb or low fat doesn't mean you need to hit "X" number. Instead, trying to find whatever amount that is low, but only as low as you can sustain and feel good on saw much better results.

It's OK to let clients find their own preferences that help adherence.

Your genotype and physiology might very well be different than the person next to you but do not under-estimate the body's ability to adapt. There are a lot of inputs here (calories, protein, fiber, carbs, meal timing, mineral status, salt intake, phytonutrients and so on) but your physiology can take a huge combination of those and get similar results to someone else as long as some really BIG inputs are covered: protein, calories, food quality and adherence.

....and the big take-away from the clients in the study?

People said the researchers helped them change their relationship with food:

-Don't eat in the car

-Don't eat in front of the TV or computer

-Buy fresh food

-Cook more

-Sit down while eating

-Making eating more social and relaxed

Clients were able to find their own way to success by changing their relationship with food and following some lifestyle changes. It is amazing how choices in terms of physchology and behavior lead to changes in calories.

Maybe so many of us have it backwards? Tied to certain dogma or protocol because of an attachment but missing out that YOUR relationship and habits regarding food can lead to the same results. And even if your path there is so much different than someone else, it doesn't mean you won't be successful.

Maybe your personal preference isn't actually the best choice? Maybe your preference is actually for a strategy that does not work for you,

Maybe your approach skips over all the pychological and emotional components which is why you can't seem to stick to your diet.

Maybe nitpicking every detail is not helpful and actually harmful.

Maybe, just maybe your diet does not need to be like a perfectly tailored suit because your physiology can figure all the details out as long as you respect the big things. And lets be honest, if you NEEDED the most highly specific and detailed personal protocol which you have not been following your whole life, you wouldn't be here right now.

Respect your physiology, respect your body's adaptability to make a lot of protocols work and respect how important it is to execute something that is actually sustainable and healthy.