Food Labels: How Accurate are they?

Food labels are there to help us make purchasing decisions. And many people, particularly those concerned with eating well, rely on the information of food labels to determine the relative healthiness of a particular food product.

These food labels are also there to keep the manufacturers honest, requiring them to be transparent in what their products are made of. But just how honest do these manufactures have to be to meet food label requirements?

US Label Requirements

In general, there are two types of labels: legally required labels and industry-provided labels.

The legally required labels are those you’re accustomed to seeing on the back of packaging. These are the labels that are governed by laws and regulations.

The laws most often control the labeling of:

- Ingredients

- Nutrition information

- Country of origin and/or manufacturer

- Other relevant health, safety, and/or agricultural information, such as the grade of beef or eggs; whether the food has GM ingredients (in some areas); etc.

The United States has very strict regulations regarding label display. Below is an example of the required US label specifications.

.png)

While these types of labels are mandatory, the other type -industry-provided labels - are not legally required. Instead, they are left to the discretion of the manufacturer. Industry-provided labels are usually shown on the front of the package. And since they are only loosely regulated by government agencies, they are a bit of a grey area in terms of accuracy.

Where do manufacturers get their nutritional information?

Since food-manufacturing companies are creating their own labels, we have to trust that the information they provide is factual. But have you ever wondered where they get that information?

For nutrition information labels, companies usually either test a food “in-house” at a food lab or they send it away for analysis.

And oftentimes the new food isn’t even tested. Instead, companies rely on the existing information they have in their nutrition software programs. How often food is re-analyzed depends entirely on company protocol.

The Role of the USDA

The United States Department of Agriculture, or the USDA, is the executive federal department responsible for developing and executing federal laws related to farming, agriculture, forestry, and food.

The USDA is also home to the mega USDA Nutrient Database, containing nutrient data on over 7,600 foods. However, there are several limitations within the database that make it impossible to rely on it for the most accurate and up-to-date nutritional information.

For instance, the USDA doesn’t have a budget for food item analysis. Therefore, they are limited to testing only 60-70 foods per year.

And since it’s so expensive to maintain database information, the USDA often generates a “generic” listing for popular foods like frozen cheese pizza. So if you buy a unique or small branded pizza, the USDA’s nutritional database information may not align with that specific brand.

The USDA is also known to collaborate with other departments, so not all USDA nutritional information came directly from the USDA itself. For instance, they get their beef and pork nutritional data from the beef and pork industries, rather than analyzing it themselves.

Each individual lab in collaboration with the USDA has its own strengths and weaknesses, making it impossible to generate consistent information.

Data Inconsistencies

In fact, one of the main problems with food labels is the inconsistency or lack of clarity in the terminology.

To start, terms that are controlled for one industry may not be controlled for another. For instance, while the USDA controls the term “natural,” it doesn’t apply to everything. You can’t label meat or poultry items with the term “natural,” yet you can use the term on to a granola bar made with high fructose corn syrup and hydrogenated oil – doesn’t seem right does it?

Terms can also be confusing and up for interpretation. For example, consumers may read the term “juice” and assume the product is the freshly squeezed liquid from a fruit. However, if a product uses the term juice it could mean any number of things: it could be a blend of juices, something that was freeze-dried and then reconstituted, or something made with a little bit of juice and topped up with water and flavoring.

Another interesting concept is technology’s role in the food industry. For instance, technology is now making it possible to derive new substances from existing foods or plants. That makes it increasingly easy to blur the line between “natural” and “artificial.”

Food labels can also be misleading. For example, a food can be labeled “low fat” if there are only a few grams of fat in the recommended serving size. But it’s the manufacturer that creates the serving size in the first place. They can easily create a miniscule serving size just so they can use the term “low fat,” when in reality a normal-sized portion would consist of a much higher fat content than the label specifications let on.

And just because a product contains a nutrient that is good for you, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the nutrient is natural, or even good for you at all. For instance, many products make the claim that a food is “high in fiber.” However, in many cases, that fiber has been added. The original food processing has stripped the good stuff out, so manufacturers have to add it back in; and the added nutrient might not be the same as the real thing.

Manufacturers can also do things like label vegetable-based ingredients as “cholesterol-free” or sugary candies as “fat-free,” making the items sound healthier than their competitors. However, these things never actually had cholesterol or fat in the first place.

And there are other terms like “light-tasting,” “a nutritious source of fiber,” or “part of a healthy breakfast” that don’t actually mean anything in terms of their nutritional value. They are just placed the packaging so the consumer associates them with something relative to health, an outlook created solely in the consumer’s mind.

Margins of Error

Due to food variants like imprecise analytical methods, length of storage, preparation method and cooking time, the calorie count on a particular product can have a wide margin of error.

In fact, the calorie number we see on the food label can have an error margin of up to +/- 25%. Frozen foods, in particular, have been shown to contain 8% more calories than the package lists.

The prevalence of healthy restaurant menus has increased recently as well, with many menus even showing the calorie count of each item. However, researchers have discovered that restaurant food labels can be off by 100-300 calories.

While these slight inconsistencies may not be a major deal for a one-time meal, if you’re trying to count calories and each meal is consistently off by 200 calories it can really add up.

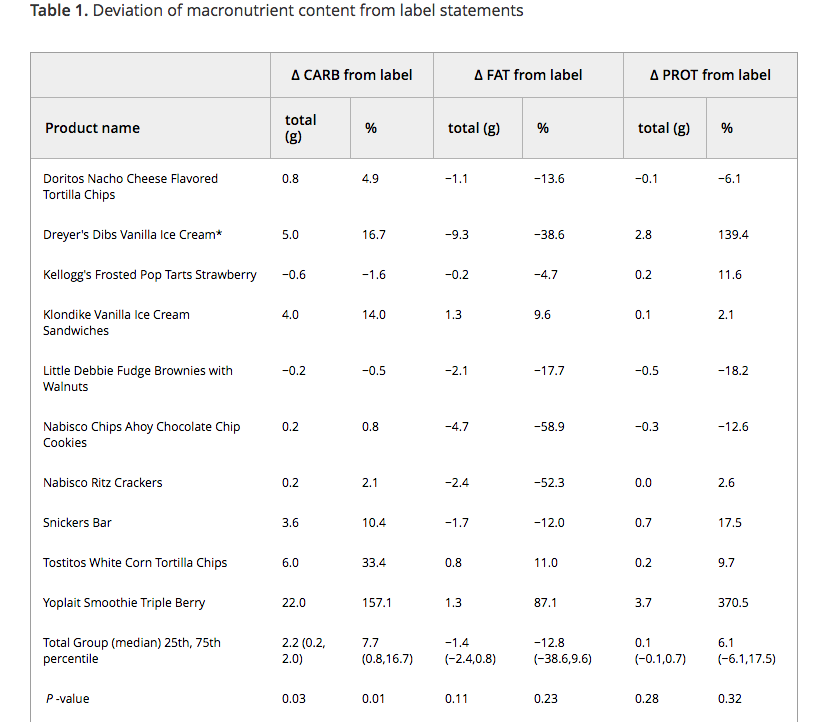

A recent study on the accuracy of food labels, conducted by the research journal, Obesity, tested 10 popular snack items to see just how “accurate” the food labels really are. Results are shown in the table below.

As you can tell, no food label is 100% accurate.

Food labels are there to serve as a guide, and they can be very helpful in food purchasing decisions. Just keep in mind manufacturers are trying to sell their food. And many are going to do what they can to portray their food as a healthy choice.

The best way to make informed decisions is to stay educated as a consumer and if you keep this info in mind you’re well on your way!

Sources:

Jumpertz, R., Venti, C. A., Le, D. S., Michaels, J., Parrington, S., Krakoff, J. and Votruba, S. (2013), “Food label accuracy of common snack foods.” Obesity, vol. 21, no. 1, pp.164–169.

Scott-Dixon, Krista. “Food Labels Part 1: What's on Your Food Label?” Precision Nutrition, 15 Dec. 2016, www.precisionnutrition.com/food-labels-part-1.

Scott-Dixon, Krista. “Food Labels Part 2: Truth, Accuracy, Usefulness of Label Claims.” Precision Nutrition, 11 Nov. 2015, www.precisionnutrition.com/food-labels-part-2.