Calories: Everything You Didn't Know

I think we need to go deeper into the calorie chasm. When you've got some light directly in front of you it becomes easier to understand what it is you're looking at. But often we're shining a flashlight into this huge open space that reveals there's so much beyond the immediate. Maybe we can make out some shadows or shapes but we can't always tell what they are.

And aside from trying to wax poetic, this really does explain a lot of science. The more you know, the more you realize you don't know. But even with all the complexity that is the human organism we still have to interact with things on a macro scale. Essentially, whatever you might know about ATP production, metabolic adaptation, leptin etc it still comes down to putting some food in your mouth. The macro level is where WE live. But sometimes looking at things from only the 400 foot view and assuming that everything comes down to 2+2 = 4 regardless of the situation can get us into some trouble.

Is there a limit to calories you can burn?

Logic might tell you that if you just moved more, like walked 16 hours per day for weeks and weeks on end, you'd be expending WAY more calories than you are now, you'd probably expect to lose some body fat too - after all it should stand to reason that moving more means more calories burned. And this is true, up to a point.

There's something called the Constrained Total Energy Expenditure Model which essentially puts forth that the more you exercise, the more calories you burn....but only up to a point. And as a coach and talking to other coaches, you see and hear this in practice. Get someone walking 3,000 steps per day to walk 10,000 and they'll lean out. But get someone walking 10,000 steps to hit 20,000 and you might find NOTHING happens. Hmm, head scratching for sure.

In the Constrained Total Energy Expenditure Model we see that the human body has mechanisms in place to keep you from simply expending calories more and more as you move more, and this makes sense for survival. If you had to move and hunt endlessly to eat and survive you'd actually be working against yourself if this Model wasn't true. The scenario might be you're hungry and you game is scarce. If you expended a gigantic number of calories to simply track, hunt down and kill some meat you might be too weak, small and tired to actually pull off the job. At a certain point you need to compensate in other areas with energy expenditure so you don't fade away into nothing.

In 2016, Pontzer et al conducted a study where 332 men and women subjects from 5 different global populations were evaluated for fat free mass, anthropometry, physical activity and energy expenditure. They also wore activity trackers and consumed a labeled water which tracked energy expenditure during the trial. Here's some really interesting findings:

- Anthropometry and fat free mass (basically ho big and muscular you are) was the primary determinant of energy expenditure

- Activity level from exercise and daily movement seemed to top out around 600 calories per day even when moving more

- There was a marked rise in energy expenditure among those who went from moving very little to moving around moderately

- The rise in expenditure topped out however in the 40% of people who moved even more

- Resting metabolic rate was NOT correlated with activity (meaning your metabolism isn't higher just because you exercise more)

What researchers did conclude is that the are of course, differences among people in energy expenditure even among the same size and activity level. And this comes back to something I've written about ad nasueum: N.E.A.T. All the movement associated with postural changes, fighting gravity, fidgeting, tapping etc make up a highly individual and significant part of total daily energy expenditure.

What's so cool about this is that is shows across multiple continents, populations, lifestyles and activity levels, our energy expenditure is not THAT much different from one another, even when we exercise a lot. Major differences therefore come down to how large and muscular you are (with men seeming to still expend more calories than women even when adjusted for size) and your individual level of N.E.A.T.

When we see that humans and non-human species alike show drops in ovarian activity, estrogen production, basal metabolic rate, lactation, repair and growth when exercise reaches a threshold it points to the fact that more exercise is not the answer for leaning out. It simply doesn't work linearly and we have so many mechanisms in place to protect us from doing so.

The Cold Hard Truth of The Biggest Loser

Want a practical example of why this approach doesn't work? Lets look to the biggest loser and everything it does to hurt people in the name of sensationalism. Great, you're screaming at a morbidly obese person to keep exercising 15 hours a week when they have literally never exercised....yeah I see that being positive long-term. Ugh.

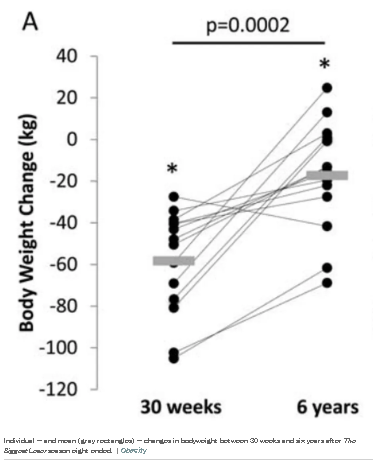

In 30 weeks of following the diet and exercise plan during the biggest loser, all 14 contestants in question below lost a lot of weight. That's awesome and I commend them for all their effort. But when we pull back and look at what happened over the course of the next 6 years, it isn't pretty.

Check out the chart below. Thirteen of the fourteen contestants gained all of their weight back and then some. Not only that but the contestants were all expending on average 500 calories per day LESS than what they should have been based on size and activity level. Perhaps most sad and frustrating is these people had such significant drops in leptin, a hormone released by your fat cells that signals fullness and helps regulate appetite. Essentially the more fat you have, the higher leptin is which should tell you you're full and satisfied which would make eating fewer calories easier.

But because of the extreme restriction in calories and over-exercise, the blood work of these contestants showed an almost complete drain in their leptin levels and at the 6 year mark? They only saw a 60% restoration of leptin. So these people had been totally screwed because the hormone which should be helping them control hunger had crashed to levels that left them hungry all the time despite weighing less.....and then despite gaining their weight back.

Is There A Thrifty Gene?

How is it that despite massive reductions in calories and a non-science term "shitload of exercise" not result in lots of lost weight?

The Thrifty Gene hypothesis states that our genetic coding has alleles that favor fat storage in times of famine as well as decreased energy expenditure. It posits that survival and reproduction are the main goals of our organism which would sacrifice how awesome your abs looked in favor of being able to survive long enough to reproduce. But other scientists don't agree, with John Speakman (an epigeneticist) writing:

"If the thrifty alleles provide a strong selective advantage to survive famines, and famines have been with us for this period of time, then these alleles would have spread to fixation in the entire population. We would all have the thrifty alleles, and in modern society we would all be obese. Yet clearly we are not. Even in the most obese societies on earth, like the United States, there remain a number of individuals, comprising about 20% of the population, who are stubbornly lean. If famine provided a strong selective force for the spread of thrifty alleles, it is pertinent to ask how so many people managed to avoid inheriting these alleles."

What we're looking at here is the question: if we've survived so long through so many periods of famine, wouldn't it make sense that we would all have thrifty genes? And if so, in a time where we move less and calories are abundant, why aren't we all overweight?

It's More Than Just Calories In vs Calories Out

Metabolic Syndrome is a disease associated with a high waistline, high blood sugar, cholesterol and triglycerides as well as increased blood pressure. Some people seem to be predisposed to these factors from genetics. But our lifestyle and environment play a large role.

In my days of working with adults with mental illness, I attended a lot of training on understanding how this disease affects people. While there are always unanswered questions it is clear that some people are pre-disposed through genetics to having certain mental health issues. But not all people are affected the same; environment plays a huge role as well as having stability, structure, friends, family, proper nutrition and being active. While I couldn't scientifically measure these outcomes in my clients I observed over and over again how people's mental health improved when they got a job, had some money, left toxic relationships, joined support groups and generally improved their environment.

So if restricting calories and over-exercise isn't a one-stop shop for fixing all your problems, what are the major contributing factors to combating obesity? While I certainly don't have all the answers here's some things that create a very good environment for optimal health:

- Getting sun in the morning

- Sleeping 7-9 hours a night with good sleep hygiene

- Eating breakfast

- Controlling calories

- Walking 10,000 steps per day

- Hydrating

- Consuming an optimal amount of Omega-3s and fiber

- Eating adequate protein

- Consuming vegetables

- Avoiding high;y processed foods an exposure to environmental toxins

There's more, probably a lot more. But these facets are things many people simply do not do. When you have a baseline of genetic predisposition to being obese or having certain health issues, the above bullet points become even more important. It's kind of like salt intake: for most of us - it doesn't matter if we eat more or less, research tends to show that our blood pressure is not that affected. But if you have a predisposition to high blood pressure then salt intake matters a whole lot more.

Plus, All The Stuff You Don't Think About

In my last post I discussed how people tend to reward themselves with more calories when exercising hard, they might move less the rest of the day after strenuous exercise or they might simply be all-around more hungry with high intensity activity. People also tend to overestimate how many calories they burn and underestimate how many calories they consume, which is tough to make the whole calories in vs calories out equation work.

We know that exercise is super potent at improving health markers. Insulin resistant individuals see improved blood sugar control post-workout because of non-insulin mediated glucose uptake. Blood pressure improves with exercise. Lower resting heart rates. But the calorie thing never seems to work the way we want it to. Doctor Yoni Freedhoff, an obesity expert wants us to think about exercise like this:

By preventing cancers, improving blood pressure, cholesterol and sugar, bolstering sleep, attention, energy and mood, and doing so much more, exercise has indisputably proven itself to be the world’s best drug – better than any pharmaceutical product any physician could ever prescribe. Sadly though, exercise is not a weight loss drug (emphasis mine), and so long as we continue to push exercise primarily (and sadly sometimes exclusively) in the name of preventing or treating adult or childhood obesity, we’ll also continue to short-change the public about the genuinely incredible health benefits of exercise, and simultaneously misinform them about the realities of long term weight management.

It comes back time and again that exercise does a lot of cool stuff for our health. We make physical, chemical and neurological adaptations to it that specifically meet the demand imposed on us. But massive calorie expenditure is generally not one of them.

The Adaptations We Do Make

Check out the table below which I give credit to ptDirect for assembling. It shows some of the adaptations we see when we engage in anaerobic and aerobic exercise.

Physiological adaptation to high intensity, short duration types

Strength, power, speed and hypertrophy training utilize the anaerobic energy pathways predominantly so we see certain metabolic adaptations with these training types such as:

Ability to produce ATP without O2 |

|

Anaerobic enzyme activity |

|

Physiological adaptation to longer duration training types

Aerobic fitness, anaerobic fitness and muscular endurance are increasingly dependent on oxygen for energy as they tend to be longer duration with less rest. Because of this different metabolic adaptations occur, such as:

Temperature regulation |

|

Body acidity balance |

|

Aerobic enzyme activity & production |

|

Lactate removal |

|

You don't need to read through all of them to get the gist. When you engage in repeated activity, you become more efficient at a physical, chemical, enzymatic and neurological level. These processes are calorie driven through the use of ATP energy derived from food we eat. So if we are becoming more efficient the longer we engage in something, then we will also be using fewer calories to power those processes. This is to reduce stress on the system and meet the imposed demand so we can tolerate it better in the future. This applies whether it's regulating temperature, increasing a muscle's cross sectional area or using glucose to contract muscle fibers.

In the end, I think Doctor Yoni Freedhof's words ring simple and true. Use exercise for the health outcomes, not weight loss.

If I've repeated it once, I've repeated it a thousand times: get all the lifestyle factors in order and THEN use nutrition to create your calorie deficit. It is the way that works. It works sustainable and it works in the most health-driven direction. The beach season will come and go with many people crashing and burning for the 100th time. But here is a mountain of evidence showing the path to weight loss done the right way, are you ready to walk it?

References:

https://www.cell.com/current-biology/fulltext/S0960-9822(15)01577-8

https://www.vox.com/2016/5/18/11685254/metabolism-definition-booster-weight-loss

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3771367/

https://www.vox.com/2018/1/3/16845438/exercise-weight-loss-myth-burn-calories

https://www.ptdirect.com/training-design/anatomy-and-physiology/chronic-metabolic-adaptations-to-exercise